Main Second Level Navigation

This Graduate Student is Fostering Public Trust in Science, One Selfie at a Time

On any given day, with a smartphone in hand, Samantha Yammine might be debunking science myths, arguing why evolution works or giving career advice to aspiring scientists, all the while running experiments to complete PhD. And taking selfies.

Yammine, who studies how the brain is formed in the laboratory of Professor Derek van der Kooy, of the Department of Molecular Genetics and Donnelly Centre, engages daily with her massive social media following—she has more than 14,000 followers on Instagram and Twitter combined—through stories about her own research and on all things science.

This past August, Yammine and fellow online science communicators have launched Scientist Selfie Project, a crowd-funded social media experiment that aims to find out what makes a scientist trustworthy and how this knowledge can be used to give the public trust in science a much-needed boost.

"Compelling science communication requires more than just factual information, it requires a compelling speaker too, and one of the most important components is trust" - Samantha Yammine, PhD candidate

A recent survey commissioned by the Ontario Science Centre, revealed that almost half of Canadians believe that science behind global warming is unclear and one in five Canadians still think the long-discredited link between vaccines and autism is true. Overall, one in four Canadians said that science is a matter of opinion.

The lack of trust could make it difficult to make informed decisions on a range of topics from climate change to public health.

Another study found that, in the U.S. at least, the public sees scientists as knowledgeable but not trustworthy, similar to the way lawyers are perceived. Adults in the U.S. have also been reported to see scientists as “robot-like and lacking emotions, as well as valuing knowledge over morality and being potentially dangerous”.

“I think we scientists are partly to blame,” says Yammine. “Most of our research is funded by public money but we don’t often share the findings of our research back with the public. And when we do, we don’t always do it in the best way. Compelling science communication requires more than just factual information, it requires a compelling speaker too, and one of the most important components is trust,” she says.

The Scientists Selfie is led by Paige Jarreau, science communication researcher from Lousiana State University (LSU). Yammine has joined her team alongside Becky Carmichael, science coordinator at LSU, Daniel Toker, PhD candidate at the University of California, Berkley and Imogene Cancellare, PhD candidate at the University of Delaware.

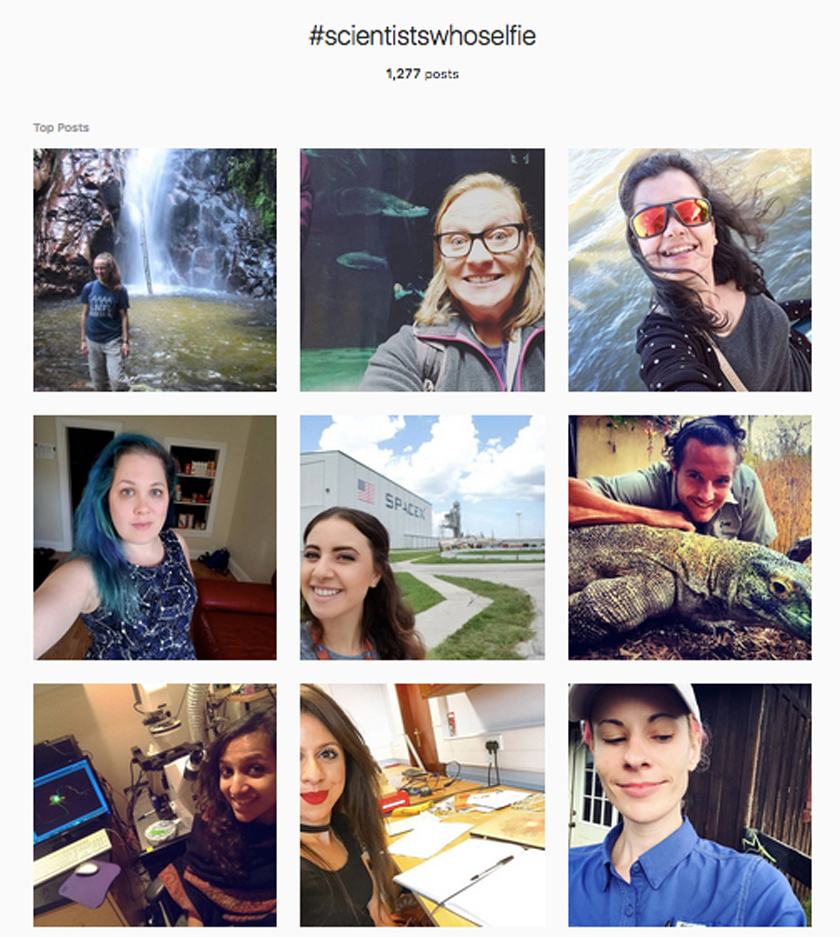

Using a #ScientistsWhoSelfie hashtag, the team launched a social media campaign to promote their study, soliciting more than 1265 images from scientists all over the world. Posted on Instagram, the images show researchers at work, be in the lab or in the field. One image shows, for example, a researcher in a lab holding a bucket full of ice for keeping reagents cool. In another image, a researcher is handling a venomous snake in a jungle.

Using a #ScientistsWhoSelfie hashtag, the team launched a social media campaign to promote their study, soliciting more than 1265 images from scientists all over the world. Posted on Instagram, the images show researchers at work, be in the lab or in the field. One image shows, for example, a researcher in a lab holding a bucket full of ice for keeping reagents cool. In another image, a researcher is handling a venomous snake in a jungle.

The photo of each scientist and their research object, both a selfie and a snaphot taken by another person, will be accompanied with a picture of the research object alone. All three images will have the same scientific caption and the public will then be the asked to rate each researcher’s trustworthiness, warmth and competence based on their gender, age, skin colour and whether or not the image was a selfie.

The data should offer insights into whether or not, say, a female scientist who takes a selfie at the lab bench is seen as equally warm and competent as a male. Or, if, for example, selfies increase warmth but decrease perceived competence.

Does Yammine think men and women will be judged differently? “My prediction is that unfortunately young females who selfie will likely be rated as less competent,” she says.

Nothing irks Yammine more than when people make assumptions about her based on the way she looks. With an unapologetic fondness for fashion and makeup, she found it “annoying that a lot of people who display more stereotypically feminine traits like me don’t get treated with the same automatic respect as my other colleagues do.”

Nothing irks Yammine more than when people make assumptions about her based on the way she looks. With an unapologetic fondness for fashion and makeup, she found it “annoying that a lot of people who display more stereotypically feminine traits like me don’t get treated with the same automatic respect as my other colleagues do.”

That’s not to say that the beauty industry is off the hook—Yammine has openly criticized an advertising campaign by a makeup company urging girls to “Skip Class, Not Concealer.” She responded with the #SkipBenefitNotClass campaign, calling on the public to boycott the company, which was seen by millions across Twitter and Instagram.

Through the Scientist Selfie project and her own social media posts, Yammine is shattering the stereotype of a typical scientist as white and male in a way that could help attract more women into STEM.

As a vocal supporter of the Naylor Report, authored by former U of T President David Naylor and commissioned by the federal government, and which advocates for stronger support of basic research in Canada, Yammine has helped raise awareness among her social media followers about the importance of basic science—exploratory science that is the root of all progress in society but takes time to bring return on investment.

“Basic biology research is losing a lot of funding and so I think I can directly do something about that by using my passion for teaching and communicating to get more people more excited about supporting basic research,” she says.

With more than 250 posts on Instagram, Yammine has covered a range of topics: from the perplexing complexity of the brain, to solar eclipse, to science policy and female scientist role models—and many more.

And with enthusiasm like that, scientists might just have a chance of winning the public back.

The Scientists Selfie is being crowdfunded on Experiment platform.

Please follow us on Twitter to keep up with Donnelly Centre news.

News